Getting Started¶

Dependencies

Apart from the python standard library, we require Numpy, available at http://numpy.scipy.org.

Installation

If you feel comfortable manually installing python libraries, feel free to do so - the module is readily importable from ./laspy/, so adding this directory to your sys.path should suffice. Otherwise, the easiest way to get set up is to use setuptools or distribute.

Distribute is available at: http://pypi.python.org/pypi/distribute.

- Once you have that installed, navigate to the root laspy directory where setup.py is located, and do:

$ python setup.py build $ python setup.py install

If you encounter permissions errors at this point (and if you’re using a unix environment) you may need to run the above commands as root, e.g.

$ sudo python setup.py build

Once you successfully build and install the library, run the test suite to make sure everything is working:

$ python setup.py test

Importing laspy

Previously, laspy documentation exclusively used relative imports. However, as outlined in PEP 328, there is a growing consensus in the Python community that absolute imports are preferable to relative imports. Moving forward, this convention will be adopted by laspy. If you wish to use absolute imports, you can:

import laspy infile = laspy.file.File("./laspytest/data/simple.las", mode="r") # ...and so on

Opening .LAS Files

The first step for getting started with laspy is to open a laspy.file.File

object in read mode. As the file “simple.las” is included in the repository,

the tutorial will refer to this data set. We will also assume that you’re running

python from the root laspy directory; if you run from somewhere else you’ll need

to change the path to simple.las.

The following short script does just this:

import numpy as np import laspy inFile = laspy.file.File("./laspytest/data/simple.las", mode = "r")

When a file is opened in read mode, laspy first reads the header, processes any VLR and EVLR records, and then maps the point records with numpy. If no errors are produced when calling the File constructor, you’re ready to read data!

Reading Data

Now you’re ready to read data from the file. This can be header information, point data, or the contents of various VLR records. In general, point dimensions are accessible as properties of the main file object, and header attributes are accessible via the header property of the main file object. Refer to the background section of the tutorial for a reference of laspy dimension and field names.

# Grab all of the points from the file. point_records = inFile.points # Grab just the X dimension from the file, and scale it. def scaled_x_dimension(las_file): x_dimension = las_file.X scale = las_file.header.scale[0] offset = las_file.header.offset[0] return(x_dimension*scale + offset) scaled_x = scaled_x_dimension(inFile)Note

Laspy can actually scale the x, y, and z dimensions for you. Upper case dimensions (las_file.X, las_file.Y, las_file.Z) give the raw integer dimensions, while lower case dimensions (las_file.x, las_file.y, las_file.z) give the scaled value. Both methods support assignment as well, although due to rounding error assignment using the scaled dimensions is not recommended.

Again, the laspy.file.File object inFile has a reference

to the laspy.header.Header object, which handles the getting and setting

of information stored in the laspy header record of simple.las. Notice also that

the scale and offset values returned are actually lists of [x scale, y scale, z scale]

and [x offset, y offset, z offset] respectively.

LAS files differ in what data is available, and you may want to check out what the contents

of your file are. Laspy includes several methods to document the file specification,

based on the laspy.util.Format objects which are used to parse the file.

# Find out what the point format looks like. pointformat = inFile.point_format for spec in inFile.point_format: print(spec.name) #Like XML or etree objects instead? a_mess_of_xml = pointformat.xml() an_etree_object = pointformat.etree() #It looks like we have color data in this file, so we can grab: blue = inFile.blue #Lets take a look at the header also. headerformat = inFile.header.header_format for spec in headerformat: print(spec.name)

Many tasks require finding a subset of a larger data set. Luckily, numpy makes this very easy. For example, suppose we’re interested in finding out whether a file has accurate min and max values for the X, Y, and Z dimensions.

import laspy import numpy as np inFile = laspy.file.File("/path/to/lasfile", mode = "r") # Some notes on the code below: # 1. inFile.header.max returns a list: [max x, max y, max z] # 2. np.logical_or is a numpy method which performs an element-wise "or" # comparison on the arrays given to it. In this case, we're interested # in points where a XYZ value is less than the minimum, or greater than # the maximum. # 3. np.where is another numpy method which returns an array containing # the indexes of the "True" elements of an input array. # Get arrays which indicate invalid X, Y, or Z values. X_invalid = np.logical_or((inFile.header.min[0] > inFile.x), (inFile.header.max[0] < inFile.x)) Y_invalid = np.logical_or((inFile.header.min[1] > inFile.y), (inFile.header.max[1] < inFile.y)) Z_invalid = np.logical_or((inFile.header.min[2] > inFile.z), (inFile.header.max[2] < inFile.z)) bad_indices = np.where(np.logical_or(X_invalid, Y_invalid, Z_invalid)) print(bad_indices)

Now lets do something a bit more complicated. Say we’re interested in grabbing only the points from a file which are within a certain distance of the first point.

# Grab the scaled x, y, and z dimensions and stick them together # in an nx3 numpy array coords = np.vstack((inFile.x, inFile.y, inFile.z)).transpose() # Pull off the first point first_point = coords[0,:] # Calculate the euclidean distance from all points to the first point distances = np.sum((coords - first_point)**2, axis = 1) # Create an array of indicators for whether or not a point is less than # 500000 units away from the first point keep_points = distances < 500000 # Grab an array of all points which meet this threshold points_kept = inFile.points[keep_points] print("We're keeping %i points out of %i total"%(len(points_kept), len(inFile)))

As you can see, having the data in numpy arrays is very convenient. Even better, it allows one to dump the data directly into any package with numpy/python bindings. For example, if you’re interested in calculating the nearest neighbors of a set of points, you might want to use a highly optimized package like FLANN (http://people.cs.ubc.ca/~mariusm/index.php/FLANN/FLANN)

Here’s an example doing just this:

import laspy import pyflann as pf import numpy as np # Open a file in read mode: inFile = laspy.file.File("./laspytest/data/simple.las") # Grab a numpy dataset of our clustering dimensions: dataset = np.vstack([inFile.X, inFile.Y, inFile.Z]).transpose() # Find the nearest 5 neighbors of point 100. flann = pf.FLANN() neighbors = flann.nn(dataset, dataset[100,], num_neighbors = 5) print("Five nearest neighbors of point 100: ") print(neighbors[0]) print("Distances: ") print(neighbors[1])

Alternatively, one could use the built in KD-Tree functionality of scipy to do nearest neighbor queries:

import laspy import scipy #from scipy.spatial.kdtree import KDTree import numpy as np # Open a file in read mode: inFile = laspy.file.File("./laspytest/data/simple.las") # Grab a numpy dataset of our clustering dimensions: dataset = np.vstack([inFile.X, inFile.Y, inFile.Z]).transpose() # Build the KD Tree tree = scipy.spatial.kdtree(data) # This should do the same as the FLANN example above, though it might # be a little slower. tree.query(dataset[100,], k = 5)

For another example, lets say we’re interested only in the last return from each pulse in order to do ground detection. We can easily figure out which points are the last return by finding out for which points return_num is equal to num_returns.

Note

Unpacking a bit field like num_returns can be much slower than a whole byte, because the whole byte must be read by numpy and then converted in pure python.

# Grab the return_num and num_returns dimensions num_returns = inFile.num_returns return_num = inFile.return_num ground_points = inFile.points[num_returns == return_num] print("%i points out of %i were ground points." % (len(ground_points), len(inFile)))

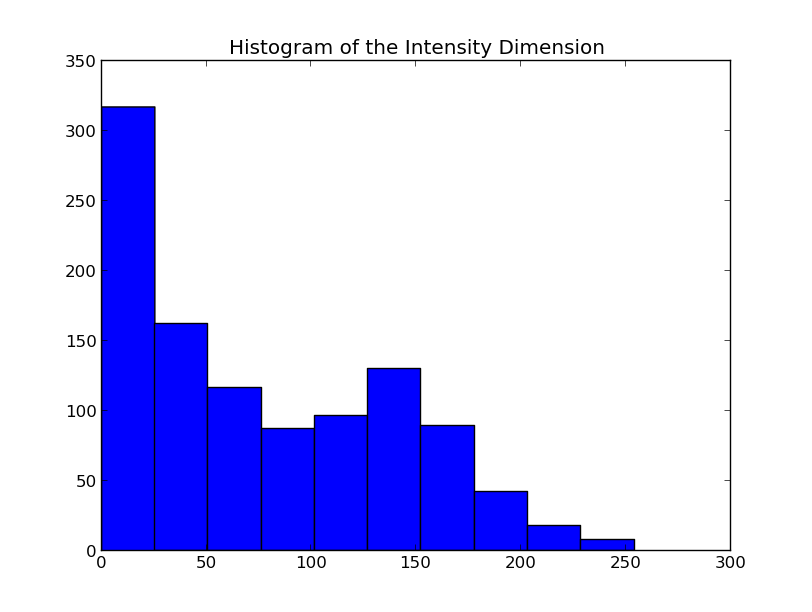

Since the data are simply returned as numpy arrays, we can use all sorts of analysis and plotting tools. For example, if you have matplotlib installed, you could quickly make a histogram of the intensity dimension:

Writing Data

Once you’ve found your data subsets of interest, you probably want to store them somewhere. How about in new .LAS files?

When creating a new .LAS file using the write mode of laspy.file.File,

we need to provide a laspy.header.Header instance, or a laspy.header.HeaderManager

instance. We could instantiate a new instance without much input, but it will

make potentially untrue assumptions about the point and file format. Luckily, we

have a HeaderManager (which has a header) ready to go:

outFile1 = File("./laspytest/data/close_points.las", mode = "w", header = inFile.header) outFile1.points = points_kept outFile1.close() outFile2 = File("./laspytest/data/ground_points.las", mode = "w", header = inFile.header) outFile2.points = ground_points outFile2.close()

For another example, let’s return to the bounding box script above. Let’s say we want to keep only points which fit within the given bounding box, and store them to a new file:

import laspy import numpy as np inFile = laspy.file.File("/path/to/lasfile", mode = "r") # Get arrays which indicate VALID X, Y, or Z values. X_invalid = np.logical_and((inFile.header.min[0] <= inFile.x), (inFile.header.max[0] >= inFile.x)) Y_invalid = np.logical_and((inFile.header.min[1] <= inFile.y), (inFile.header.max[1] >= inFile.y)) Z_invalid = np.logical_and((inFile.header.min[2] <= inFile.z), (inFile.header.max[2] >= inFile.z)) good_indices = np.where(np.logical_and(X_invalid, Y_invalid, Z_invalid)) good_points = inFile.points[good_indices] output_file = File("/path/to/output/lasfile", mode = "w", header = inFile.header) output_file.points = good_points output_file.close()

That covers the basics of read and write mode. If, however, you’d like to modify a las file in place, you can open it in read-write mode, as follows:

import laspy inFile = laspy.file.File("./laspytest/data/close_points.las", mode = "rw") # Let's say the X offset is incorrect: old_location_offset = inFile.header.offset old_location_offset[0] += 100 inFile.header.offset = old_location_offset # Lets also say our Y and Z axes are flipped. Z = inFile.Z Y = inFile.Y inFile.Y = Z inFile.Z = Y # Enough changes, let's go ahead and close the file: inFile.close()

Variable Length Records

Variable length records, or VLRs, are available in laspy as file.header.vlrs.

This property will return a list of laspy.header.VLR instances, each of which

has a header which defines the type and size of their record. There are two fields

which together determine the type of VLR: user_id and record_id. For a summary of

what these fields might mean, refer to the “Defined Variable Length Records” section

of the LAS specification. These fields are not required to be known values, however

unless they are standard record types, laspy will simply treat the body of the VLR

as dumb bytes.

To create a VLR, you really only need to know user_id, record_id, and the data you want to store in VLR_body (For a fuller discussion of what a VLR is, see the background section). The rest of the attributes are filled with null bytes or calculated according to your input, but if you’d like to specify the reserved or description fields you can do so with additional arguments.

Note

If you are creating a known type of VLR, you will still need to fill the VLR_body with enough bytes to fit the data you need before manipulating it in human readable form via parsed_body. This part of laspy is still very much under development, so feedback on how it should function would be greatly appreciated.

# Import the :obj:`laspy.header.VLR` class. import laspy inFile = laspy.file.File("./laspytest/data/close_points.las", mode = "rw") # Instantiate a new VLR. new_vlr = laspy.header.VLR(user_id = "The User ID", record_id = 1, VLR_body = "\x00" * 1000) # The \x00 represents what's called a "null byte" # Do the same thing without keyword args new_vlr = laspy.header.VLR("The User ID", 1, "\x00" * 1000) # Do the same thing, but add a description field. new_vlr = laspy.header.VLR("The User ID",1, "\x00" * 1000, description = "A description goes here.") # Append our new vlr to the current list. As the above dataset is derived # from simple.las which has no VLRS, this will be an empty list. old_vlrs = inFile.header.vlrs old_vlrs.append(new_vlr) inFile.header.vlrs = old_vlrs inFile.close()

Putting it all together.

Here is a collection of the code on this page, copypaste ready:

import numpy as np import laspy inFile = laspy.file.File("./laspytest/data/simple.las", mode = "r") # Grab all of the points from the file. point_records = inFile.points # Grab just the X dimension from the file, and scale it. def scaled_x_dimension(las_file): x_dimension = las_file.X scale = las_file.header.scale[0] offset = las_file.header.offset[0] return(x_dimension*scale + offset) scaled_x = scaled_x_dimension(inFile) # Find out what the point format looks like. print("Examining Point Format: ") pointformat = inFile.point_format for spec in inFile.point_format: print(spec.name) #Like XML or etree objects instead? print("Grabbing xml...") a_mess_of_xml = pointformat.xml() an_etree_object = pointformat.etree() #It looks like we have color data in this file, so we can grab: blue = inFile.blue #Lets take a look at the header also. print("Examining Header Format:") headerformat = inFile.header.header_format for spec in headerformat: print(spec.name) print("Find close points...") # Grab the scaled x, y, and z dimensions and stick them together # in an nx3 numpy array coords = np.vstack((inFile.x, inFile.y, inFile.z)).transpose() # Pull off the first point first_point = coords[0,:] # Calculate the euclidean distance from all points to the first point distances = np.sum((coords - first_point)**2, axis = 1) # Create an array of indicators for whether or not a point is less than # 500000 units away from the first point keep_points = distances < 500000 # Grab an array of all points which meet this threshold points_kept = inFile.points[keep_points] print("We're keeping %i points out of %i total"%(len(points_kept), len(inFile))) print("Find ground points...") # Grab the return_num and num_returns dimensions num_returns = inFile.num_returns return_num = inFile.return_num ground_points = inFile.points[num_returns == return_num] print("%i points out of %i were ground points." % (len(ground_points), len(inFile))) print("Writing output files...") outFile1 = File("./laspytest/data/close_points.las", mode = "w", header = inFile.header) outFile1.points = points_kept outFile1.close() outFile2 = File("./laspytest/data/ground_points.las", mode = "w", header = inFile.header) outFile2.points = ground_points outFile2.close() print("Trying out read/write mode.") inFile = File("./laspytest/data/close_points.las", mode = "rw") # Let's say the X offset is incorrect: old_location_offset = inFile.header.offset old_location_offset[0] += 100 inFile.header.offset = old_location_offset # Lets also say our Y and Z axes are flipped. Z = inFile.Z Y = inFile.Y inFile.Y = Z inFile.Z = Y # Enough changes, let's go ahead and close the file: inFile.close() print("Trying out VLRs...") inFile = File("./laspytest/data/close_points.las", mode = "rw") # Instantiate a new VLR. new_vlr = laspy.header.VLR(user_id = "The User ID", record_id = 1, laspy.header.VLR_body = "\x00" * 1000) # Do the same thing without keyword args new_vlr = laspy.header.VLR("The User ID", 1, "\x00" * 1000) # Do the same thing, but add a description field. new_vlr = laspy.header.VLR("The User ID",1, "\x00" * 1000, description = "A description goes here.") # Append our new vlr to the current list. As the above dataset is derived # from simple.las which has no VLRS, this will be an empty list. old_vlrs = inFile.header.vlrs old_vlrs.append(new_vlr) inFile.header.vlrs = old_vlrs inFile.close()